Translators and interpreters use their knowledge of two or more languages and cultural meanings to translate or interpret texts and conversations from one language to another, to enhance communication across cultures and the parties involved.

The difference between a translator and an interpreter is how they perform their job duties. Translators convert one language to another in a written form (e.g., documents, film subtitles, books). In contrast, interpreters translate languages simultaneously through spoken words (e.g., meeting with clients in-person and attending negotiations). Also, on many occasions, interpreters play an essential role as assistants and troubleshooters behind the scenes.

For nearly 40 years, I performed both functions as a translator and interpreter of Russian for various government institutions, businesses, non-profit organizations, and private individuals. Although interpreting languages is a highly technical skill, it is also a communication task that ensures a successful cross-cultural engagement and understanding for all. In fact, unqualified interpretation can create a conflicting outcome and cross-cultural misunderstanding for those who rely on interpretation; and vice versa—a professional interpretation can lead to a successful outcome.

For example, in 1977, during U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s visit to Poland, a segment of his speech was incorrectly interpreted. The interpreter said President Carter wanted to learn about the Polish people’s “desires for the future,” which translated into a sexual desire for the then-Socialist country, instead of the country’s “aspiration for the future,” a hope or ambition of achieving something in the future.

From 1946 to the mid-1980s, Alaska was closed for Soviet citizens, except for some scholarly exchanges between two regions. During this time of the “Iron Curtain,” both nations were an enigma to one another and often subjected to dubious behaviors toward each other.

Nevertheless, initial visits of official Soviet delegations to Alaska in the 1980s and early 1990s, generated an enormous interest and excitement among all spectrum of Alaska’s residents (e.g., government institutions, businesses, educators, private individuals, etc.). In my practice as an interpreter in Alaska, three different occurrences clearly exemplified the complexity of responsible interpretations and the need for quick adaptation to an unpredictable turn of events.

The governor of the Magadan Region of the former Soviet Union, Vyacheslav Kobets, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Magadan Region, and a special envoy from Moscow visited Alaska in February of 1989. The delegation of Soviet officials and I, as an interpreter, were invited to visit the Alaska Legislature in Juneau.

ALASKA WATCHMAN DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX

While at the guest gallery of the House Chamber, then-Speaker of the House Sam Cotten welcomed the Soviet delegation. Unexpectedly, Governor Kobets stood up, pulled out several long-typed pages of text and, from the gallery, began addressing the Legislature in the Russian language.

The legislators and I were not prepared for such a turn of events. I immediately began a simultaneous translation without prior familiarity with the text. Kobets’ presentation lasted about 40 minutes and, evidently, it delayed the working agenda of the House’s session that day.

Nevertheless, all legislators listened to Kobets’ presentation via my translation attentively and patiently. I noticed, however, that the special representative from Moscow was visibly nervous during the presentation; he understood that Kobets lacked knowledge of the proper protocol.

In the early stages of the Russian-Alaskan exchanges, both sides went through a learning curve of reciprocal cultural and business familiarity with each other—sometimes quite awkward and sometimes humorous. My friend David Marshall was an economist in Juneau in the 1980s and 1990s. He, as well as many Alaskans, traveled to the Soviet Union on several occasions with the purpose of establishing a lucrative business with Russian entrepreneurs. In the early-1990s, he got acquainted with Boris from Magadan; Boris appeared to David as an enthusiastic and well-connected businessman. When Boris arrived in Juneau, they met at the Fiddlehead Restaurant to discuss David’s carefully drafted business proposal for a joint venture. (Evidently, David and Boris previously discussed establishing a financial investment company—a hedge fund—prior to the meeting in Juneau).

At some point during the meeting, Boris leaned toward David and suggested, “Listen, David, why complicate our business with this hedge fund? Instead, we can simply sell shampoo and make a good profit.” For a moment, David was puzzled by this unexpected suggestion. “And can you explain to me where and how the profit will come from by selling shampoo?” David asked suspiciously. “It is simple. We will dilute the shampoo with about 20 percent water,” answered Boris with a smirk smile. “In Magadan, no one will even notice a difference, and the product will fly off the shelves very quickly,” he continued.

Suddenly, David erupted like an ancient volcano after centuries of “hibernation,” angrily tearing the business proposal in pieces and throwing it in the air like party confetti. All the guests in the restaurant turned their attention toward our table, each with an obvious curiosity about the commotion. All I could think at this moment, “There goes $60 per hour for my interpretation services.” Indeed, this was last meeting between these two enthusiastic businessmen. I was not paid for my efforts, and I was not daring enough to ask for it.

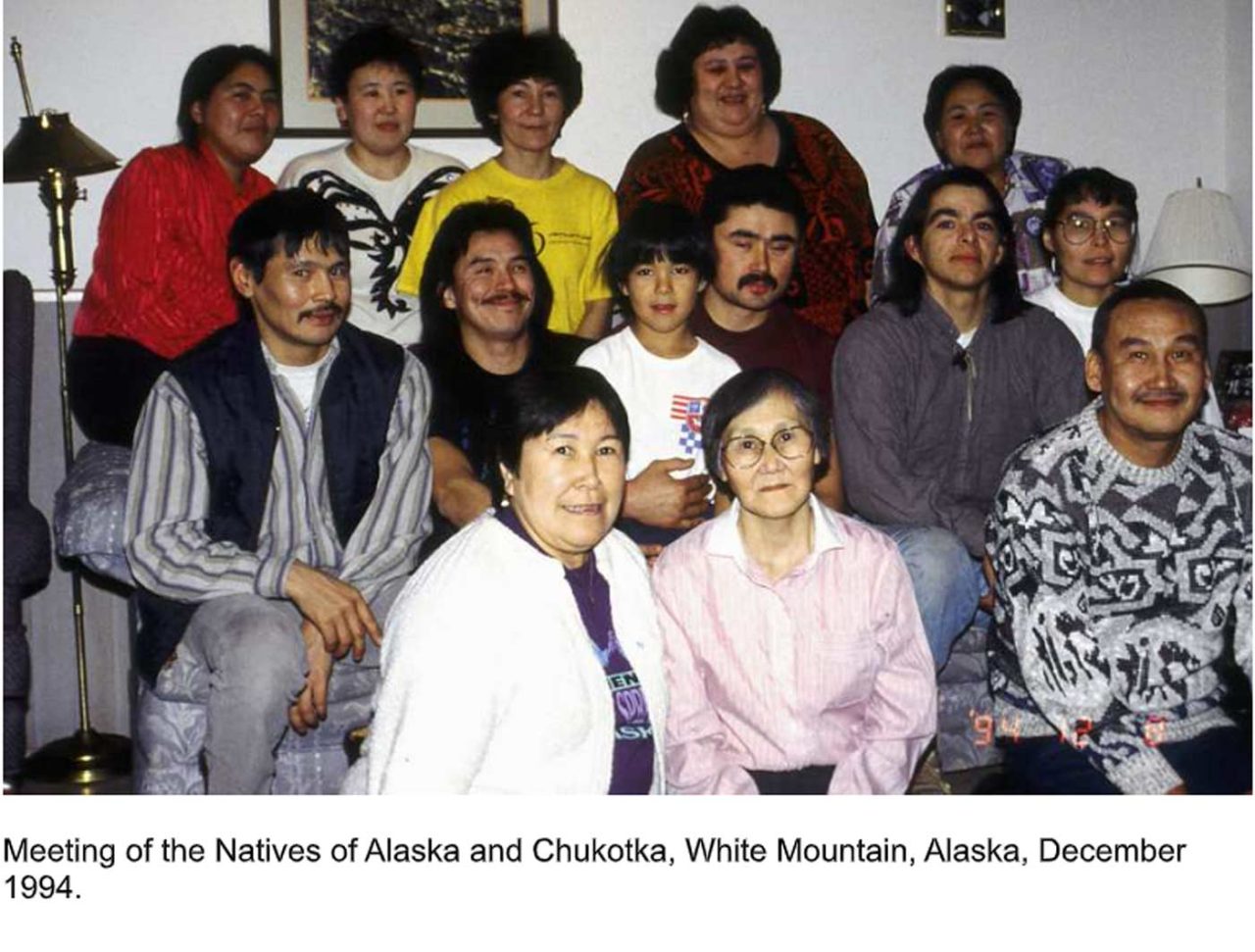

In December of 1994, I was hired to interpret for meetings between Natives of Alaska and Natives of the Russian Far East. The meetings were held in White Mountain Village and Shishmaref Village of Northwest Alaska under auspices of the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services and Eurasian Foundation.

The topics of the meetings were rather dramatic, emotional and urgent among Natives of both regions — alcoholism, diabetes, botulism, suicide, family abuses, mental illness, and various health-related issues. The participants shared their painful experiences, and I did my best in interpreting the information. Although Alaska Yupik and Inupiaq have close cultural and linguistic similarities with the Siberian Yupik and Chukchi, they could not fluently understand each other’s unique languages.

At one point of working with the Natives in Shishmaref Village, an elderly Alaskan Yupik woman approached me with a concern about my interpretations, “I do not like your translation,” she declared boldly. “Why?” I asked. “You do not translate our feelings,” she answered in a demanding voice, staring directly into my face. “I understand how you feel but interpreters translate words, sentences and contents, not emotions, feelings or attitudes,” I responded delicately. Her body language and facial expression gave me a distinct impression that she did not appreciate my explanation or my role at the meeting. Indeed, after 10 days of working above the Arctic Circle in December, I was relieved to return to my home in Juneau.

In my observation, the majority of the left-leaning progressive activists had impulsively initiated poorly-thought out exchanges with the former Soviet Union in the 1980s and early 1990s. Ironically, the left-leaning progressive activists went in the opposite directions after Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 in supporting harsh and irrational sanctions upon the Russian Federation; which ultimately led to the rise of radical nationalism in Ukraine and, subsequently, led to the Russian-Ukrainian war of February 2022 until today.

After all, how many decades will it take to restore friendly and constructive relationship with our neighbor—Russia? It will take more than a skillful interpreter, it appears, because the two sides are far beyond the translation of “feelings” at this point in the conflict.

The views expressed here are those of the author.

4 Comments

No Experience Needed, No Boss Over il Your FD Shoulder… Say Goodbye To Your Old Job! Limited Number Of Spots

Open……. Join.Payathome9.com

What an excellent post! Reading it was really educational for me. You provided extremely well-organized material, and your explanations were both clear and brief. Your time and energy spent on this article’s research and writing are much appreciated. Anyone interested in this topic would surely benefit from this resource.

I think that there is a lot of hurt within the native communities. Things done without satisfactory explanation of why. Hard to give a good explanation of why “white man” was doing things a certain way, when, now, we find out that any action taken was not for the benefit of natives…or any other “animal.” While I can understand the distrust and the misunderstandings, there comes a point where – even the natives – need to grasp God Almighty’s word and trust HIM.

The filter is allowing spam to post, but not comments regarding the actual article.