I first arrived in America Feb. 1, 1978. An agent of the Immigration and Naturalization Services greeted me at the John F. Kennedy Airport in New York. He gave me $8, a small booklet titled “Introduction to a New Life“, a packet titled United States Refugee Program, and wished me “Good Luck”! On that same day, I traveled to Philadelphia, where my new life began as an immigrant in America.

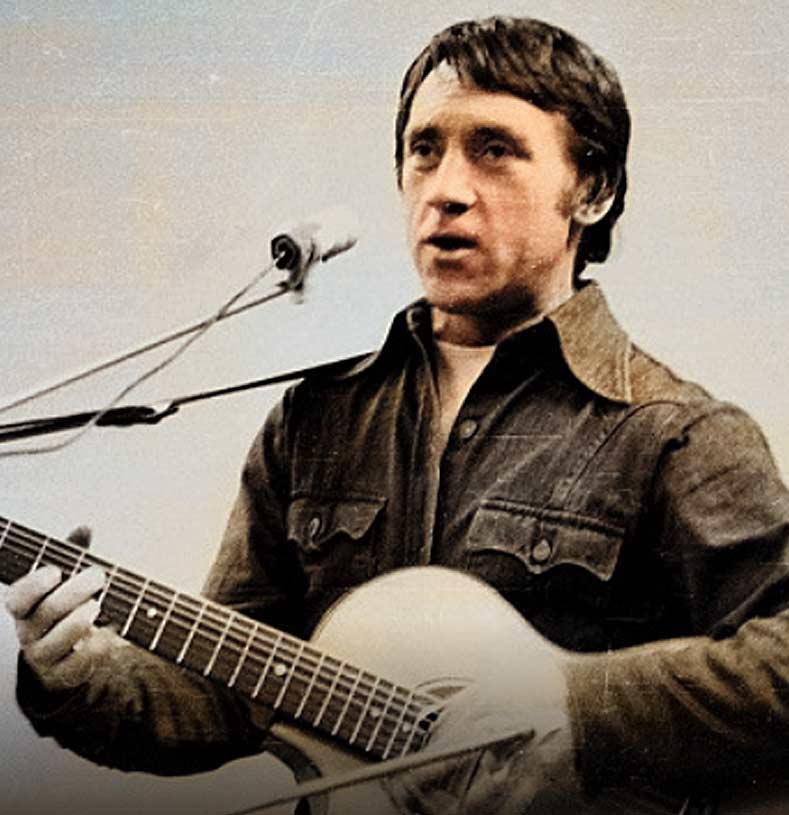

Three–four months later, a rumor went around among the Russian immigrant community in Philadelphia that Vladimir Vysotsky, a popular actor, poet and singer, would perform at the Doral restaurant in the northeast part of the city. Tickets cost $10, which at that time was a substantial sum for newly arrived immigrants. But I scraped together the money for a ticket and went to the Vysotsky concert.

I knew Vysotsky’s songs well. Having been a student of the history faculty of Kiev Pedagogical Institute, I had participated in archeological expeditions and always listened with enthusiasm, either to his own recordings, his songs around a fire, or among a small circle of friends. In the U.S.S.R., Vysotsky, an ideologically controversial character, in a majority of cases, performed at factory concert halls or in other unassuming venues and in cultural clubs. It was practically impossible to attend one of his concerts in the former Soviet Union due to a high interest for his performance or security reasons engineered by the internal police.

In the spring of 1978, some 150–200 people, all Russian immigrants (approximately 300 immigrant families lived in Philadelphia in the 1970s), were crowded into the Doral restaurant auditorium in northeast Philadelphia. Representatives of Soviet authority from the Russian Embassy in D.C. were also present, standing in various corners of the hall and looking intently over the assembled crowd. Their mere presence evoked a feeling of caution, tension and fear borne of past years in the Soviet Union.

On the stage was a stool, and near this stool one of the concert organizers had placed a bottle of vodka with a cut glass. A short time later, Vysotsky quietly came on stage with his guitar and, without looking out over the attendees in the hall, sat on the stool and turned to the audience: “Please, do not send me notes with requests. I will sing only what I want to sing.” The audience did not respond to these words; he began to perform, one song after another, without commentary and particular emotion. The concert lasted 40–50 minutes. Vysotsky did not drink the vodka.

ALASKA WATCHMAN DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX

My second, but at that time not personal, encounter with Vysotsky occurred in the summer of 1990, in Altay (mountains in Russia north of Mongolia) where, along with students of the history faculty of Krasnoyarsk University, I was conducting an archeological investigation of the Denisov Cave. Academic Anatoliy Panteleyevich Derevyanko, on behalf of the Siberian Branch of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R., had invited me to Akademgorodok (a large scientific center in Western Siberia) in Novosibirsk for three months to participate in the archeological expedition in Altay. By this time, I had already lived in America for 12 years and had become a U.S. citizen.

Vysotsky was no longer living; he had died in Moscow, with a long and sad account of his last days under the influence of many drugs, in July of 1980 at the age of 42. But he remained in the memory of those who loved his lyrics and open-minded songs. At the conclusion of the archaeological expedition, the students with whom I had worked in Altay gifted me a book of Vladimir Vysotsky’s verses titled Klich (“call” or “summons”). The book was already quite worn and, it appeared, read many times by many people. On the first page of the book the students had written: “To our friend Alex from his Soviet student historians. Denisov Cave – ‘90’.”

These were my encounters and are my recollections regarding Vladimir Vysotsky, one of the instigators and pioneers of glasnost (“the opening”) in the former Soviet Union, that took place long before Mikhail Gorbachev’s socio-economic reforms in the mid-1980s.

4 Comments

Not only are “Vaccine Passports” totally un constitutional here in the ‘remnants’ of the USA; but are 100% against our very own HIPPA laws. They will have to shackle and drug me into submission before I take this unpoven biological ‘agent’. ON the sanctity of life: even 5th graders and younger know that life begins at conception. Lastly : any nation that has committed egregious slaughter; pre meditated slaughter of its’ preborn humans has zero legs to stand on any other issue. WE have built our nation on this evil. Grandma Sharon T

How does this relate to Vysotsky? I’m not following.

This is a great story. How could you identify the Soviet embassy employees? Did they take photos of the gathered exile community? Did they in any way try to interact? Your response is appreciated.

As I recall, they were wearing a uniform and looked very intense and assertive. Everyone in the audience could tell who is who. I assume they were from the Embassy or Consulate. Or could be from the military attaché.