By Sarah Montalbano – Alaska Policy Forum

It is usually assumed that increased education funding leads to improved academic performance, but research suggests that the way financial resources are allocated is more important than the amount of money invested. The Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University has demonstrated that more money does not necessarily result in better outcomes.

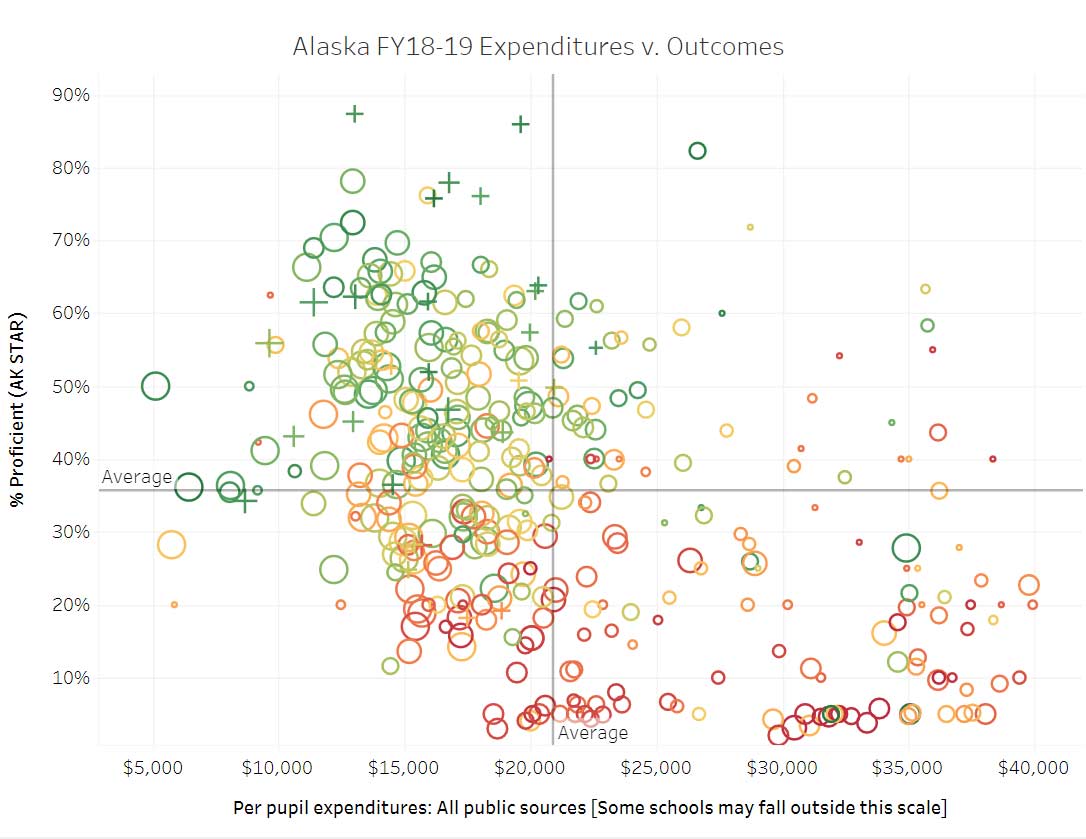

The Edunomics Lab created a useful chart, shown below, of per-pupil expenditures and proficiency on Alaska’s statewide assessment. The chart plots schools’ per-pupil expenditures in fiscal year 2018-2019 on the horizontal axis and the percentage of students proficient on the Alaska System of Academic Readiness (AK STAR) on the vertical axis. The proficiency level is an average of performance on the math and English language arts exams. Statewide, the average percentage of students proficient in a school was 36%, and the average spending per student was $20,907.

…it is essential to target effective initiatives and expand access to options that do more with less, such as correspondence schools and charter schools.

The size of a school’s bubble represents its enrollment while the color of the bubble represents the percentage of students in the school who are economically disadvantaged, which in Alaska includes those students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Charter schools are marked as plus signs rather than bubbles. The chart does not show schools with per-pupil spending higher than $40,000, although some of Alaska’s schools do spend more than that amount.

Surprisingly, as a school’s per-pupil expenditures increase, the percentage of proficient students declines. This trend, although there are exceptions, challenges the conventional belief that more funding directly translates to better outcomes. Furthermore, the chart reveals that the schools spending less than $10,000 per student not only consistently performed near or above the statewide proficiency average of 36%, but were also almost entirely correspondence schools or charter schools. Many of the top-performing schools are charter schools as well. These innovative models have demonstrated the ability to do more with limited resources.

The belief that injecting more money into schools will automatically yield positive outcomes is a common misconception. The key lies in wisely allocating funds to schools and programs that have successfully improved student performance. Simply increasing the overall budget for education is not sufficient to improve outcomes; it is essential to target effective initiatives and expand access to options that do more with less, such as correspondence schools and charter schools. More money can certainly make a difference, but funding that is absorbed by growth in administration or underfunded pension systems is not likely to benefit teachers’ classrooms, teachers’ salaries, or student outcomes.

ALASKA WATCHMAN DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX

It is essential to prioritize transparency and accountability in the allocation of education funds. As Eric A. Hanushek, a fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, said, “You can’t trust that you can just drop in a pile of money and expect good performance to come out.” Spending increases should be accompanied by a commitment to allocate and use the funds in productive ways, and transparency ensures that commitment is fulfilled. By taking a thoughtful approach to educational funding, every dollar invested can make a genuine difference in the lives and educational trajectories of Alaska’s students.

The views expressed here are those of the author.

4 Comments

i am extorted via property tax to pay for government services i dont use…Sounds like communism and socialism to me. then those govt services are not held accountable to a outcome standard or performance watermark. there is nothing about this thats right, or just. its criminal IMHO.

Finally an article pointing out the obvious – results are always obtained by innovative programs that both challenge the student and create a thirst for learning. School should never be a boring series of lectures and standard questions. Illustrating the learning targets, whether math or history or any other subject and then inviting discussion is how students get knowledge. Then putting what they have learned to use is how education really contributes to the future generations.

To improve Alaska’s public education it need to be all scrapped and started over from the ground and don’t unionize it. This way all the crummy administrators and staff only here for money have only one choice to leave a state that its money only brought them to the northern most state.

You’re confusing cause and effect. A school with a lot of kids from troubled homes — homes with substance abuse, child abuse, etc. — is going to have lower test scores. That school will also have higher per pupil expenditures because it will have more special Ed kids on IEP’s. So of course a school with lower achievement test scores will have higher per pupil costs.