Profoundly religious, the Russian people were shaken to their core by the Russian Orthodox Church liturgical reforms introduced by Patriarch Nikon (1666–1667) who, under the reign of Tsar Alexis Mikhailovich Romanov (1645–1676), had dared to correct the mistakes in the manuscripts of the Holy Books.

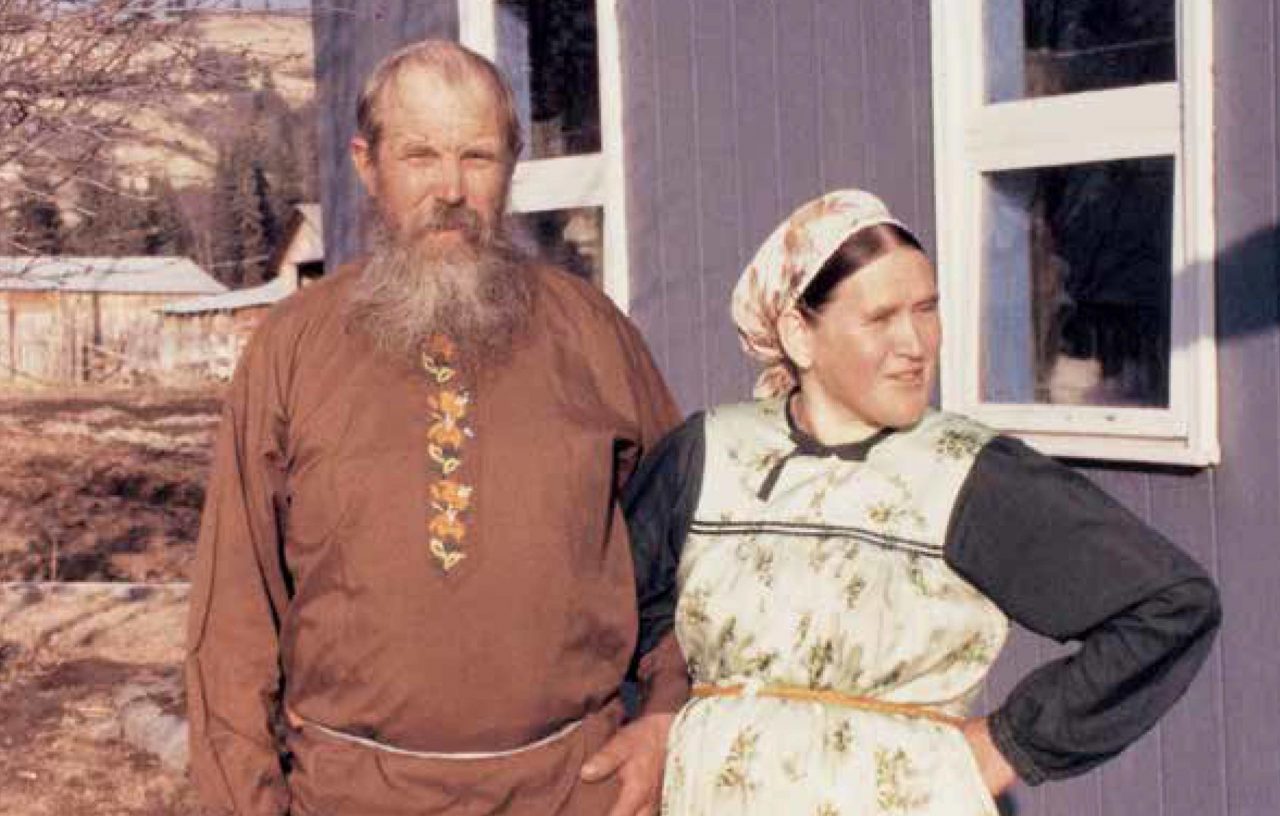

Many devout believers refused to renounce the errors of their fathers, consecrated by tradition. Numerous rural settlements of Russian Old Believers were subsequently established almost everywhere in Russia and, eventually, abroad. The dissenters did not want to base their faith on anything new except the old texts, despite the inaccuracies of the translation, done centuries ago, from Greek to Russian; and they would observe only old traditional customs and worship practices denounced by the present Russian Orthodox Church.

Eventually, persecution by the Russian tsarist government and aggressive treatment by their hostile neighbors and the State Orthodox Church forced Orthodox Old Believers into remote and undeveloped rural areas, where they quietly continued to practice their old rituals, periodically moving when threats of persecution by a hostile regime and intrusion by outsiders of different faiths and beliefs caught up with them again. Several of these groups migrated to the United States in the 1960s, settling in rural areas of Oregon and Alaska.

The history of the Russian Old Believers is the most dramatic and vivid example of a large segment of people who opposed new liturgical and worship changes and managed to preserve their 17th-century religious practices, national traditions and core cultural values, despite constant exposure to various geographic, religious, ideological, economic, and social challenges to which they have been subjected for the past 355 years.

Drawing on historical accounts and ethnographic research since 1983, I posit that the cultural persistence evidenced by Old Believer settlements in Alaska is due to the cognitive conservative rational preselection and/or rejection of culture traits and adaptive strategies that have demonstrated their survival value, cultural continuity, and “living memory” during lengthy periods of religious persecution and geographical relocations.

Since the mid-17th century, the core cultural values and ancient Orthodox institutions of Old Believers have changed very little, despite exposure to a multitude of different socio-physical environments over the course of three and a half centuries. As such, Russian Old Believer culture in Alaska remains little changed from its earlier heritage.

Of course, Old Believer culture has evolved somewhat in the past 355 years. Life in close contact to atheistic Soviet ideology, aboriginal populations of China, Brazil, the United States, Canada and the former Soviet Union, and the influence of modern technologies and cultural values of the United States and Canada have led to disobedience of traditional ways among Old Believers’ youth. Despite a value structure strongly favoring cultural persistence and stability, they have gradually institutionalized practical ideas and elements of modern technologies (telephones, automobiles, home appliances, and even television among some families) into their social structure.

Old Believers exercise a conservative rational preselection of culture traits in order to preserve their existing culture. Russian Old Believers have experienced social, economic, and ideological upheavals that permit them to embrace or resist new religious modes and cultural modernization. Old Believers have a strong sense of obligation to preserve the age-old religious rituals of the pre-reform Russian Orthodox Church. They have developed a sense of religious identity and attachment in an attempt to secure coherence in their universe of relations, both physical and social.

Temptations of the modern, secular world are a constant threat to the discipline and religious loyalty of the youth.

Certainly, Old Believers in Alaska have changed in some ways since the 1960s. The greatest changes have been in matters of material, technological and secular culture and social life, and those reflect adaptation to circumstances rather than fundamental alteration of their cultural identity.

Religious matters and values have been the most stable elements of their culture. To Old Believers, religion is not an institution parallel to economics, politics, or kinship, but the soul of their society. It is more fundamental than other elements and permeates all of them. For Alaskan Old Believers, religion is not limited to a particular sphere of life; it is all pervasive and colors everything. Religion determines their values, appearance, eating habits, the roles of children, women and other adults of their society; it shapes their social behavior and subsistence practices.

Their insistence on preserving 17th-century pre-reform rituals of the Russian Orthodox Church has resulted in persecution and constant dislocation during the past 355 years. In Alaska, they have found religious and traditional freedom, economic survival, a sense of belonging, and state protection of their cultural values. In June 1975, 59 Old Believers of Nikolaevsk village in the Kenai Peninsula became citizens of the United States.

The naturalization ceremony took place at the Anchor Point school near their homes. After the ceremony, Kiril Martushev spoke for all the villagers: “For a long time, we have looked for a place in the world where we could live our own lives and be free in our beliefs in God. We have found what we were looking for here, and that is why we decided to become citizens of this great United States.” There was scarcely a dry eye in sight when Kiril sat down.

ALASKA WATCHMAN DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX

The temptations of the modern and secular world, however, are a constant threat to the discipline and religious loyalty of the youth. In response, in early 1980s some members have moved to more remote locations of the state — Voznesenka village in the Kachemak Bay area and Berezovka village in Southcentral. Old Believers feel that if they can stay together as a cohesive community, they will be able to protect their religious freedom and their religious and ethnic identity, to strengthen their economic security, and continue to maintain control over the direction of their lives.

Consequently, the Old Believer system of communication with each other and with outsiders, and their strategy of cognitive rational preselection, migration, and boundary maintenance may present lessons and alternatives to other ethnic minorities or isolated communities in Alaska, across the United States and around the world, increasingly being subsumed by the encroachment of urbanization, rapid modernization, global corporate colonization, and Westernization.

The views expressed here are those of the author.

3 Comments

Ethnic minorities, religious refugees, and other groups segregated by a dominant society have developed and implemented strategies and tactics intended to protect their national identity, religious practices, ancient traditions, and community cohesiveness. In most cases, the tactics and strategies of these unique orthodox groups, created to secure cultural continuity and “living memory” among their members, have historic roots and have resulted from rational conservative choices of their members.

Religiously oriented Amish farmers in North America, for example, have remained mostly unmechanized and virtually self-sufficient for the past 250 years, while in rural America, in general, there has been a tendency to accept and use technological changes and inventions.

The Dukhobors, members of a religious sect derived from Russian Orthodoxy in the 18th century, currently live in rural areas of Western Canada. In defending their values of religious communism, their members exercise pacifist strategies among their adherents and condemn those who violate them. The Dukhobors’ pacifist tactics have helped to preserve them as a distinctive group and have delayed assimilation as long as the powerful trends toward social uniformity (which are deeper and less visible than those towards political uniformity) will allow.

Within the Hutterites, a Mennonite sect that originated in the 16th century in Europe, when social changes among their youth and a desire to assimilate with a dominant culture are detected, the elders tend to accept cultural innovations before the pressure for them becomes so great as to threaten the basic cohesiveness of the social system. They rewrite the rules of the society in accordance with new demands from members of their community. Rules tend to be written down only when this common consensus starts to break down.

Historically, East European Jews lived in small cohesive villages in Russia, Belorussia, Poland, Ukraine, and other regions of Europe during the tsarist regime or prior to the October 1917 Socialist Revolution in Russia. The film Fiddler on the Roof, directed by Norman Jewison, quite accurately depicts the life of Jewish families in those villages—isolated from urban centers, protective of their village boundaries and national traditions, obeying elders’ and rabbis’ advice for religious and secular matters, and following orthodox rules and traditions of Judaism. For centuries, their faith helped them survive as a nation, despite continuous hostility from their non-Jewish neighbors and oppressive governments. Today, modern Jewish families, mostly in Western urban societies, assimilate with dominant cultures at will, with the exception of certain Orthodox Jewish groups in a variety of locations.

Wonderful report ! Maintaining Ethnic Identity is Key to Religous Freedom being Maintained.! We Thank You.

My maternal Grandfather was a Lutheran. Russian Orthodoxy was gaining congregants but he didn’t allow his kids to attend though he lent chairs here in Alaska. My father’s mother was Russian Orthodox his Dad was probably Catholic. My Dad learned the Russian catechism. Then attended protestant churches as the became available.