In the past, many of my students at Alyeska Central School, the former state correspondence school based in Juneau, and my students at the University of Alaska Southeast, asked me three essential sociological questions: How do you define ethnicity and race? How do the two concepts differ? How do you define the term “minority?”

Ethnicity is a social, communal category we use to identify our heritage based on religion, geographic location or culture. It comes from shared values, shared upbringing, cultural norms, and learned behavior. Race is very much like ethnicity in that way; it is based also on shared beliefs and shared experiences. We tend to think of race as biological or genetic, but race is also a social and culturally created phenomenon.

The glue that holds us together in the United States is that we all perceive ourselves as Americans.

Ethnicity is usually more difficult to trace because when we look at someone, we can’t immediately categorize them in a certain ethnic group. I had students who thought that because they are not African-American, Latino or Asian, they have no ethnic identity. This is wrong; we all have an ethnicity.

Ethnicity allows for more inclusion (it may consist of many biological races), and race for more exclusion (only one biological race). A classic example is Israel, where there are Ethiopian Jews, German Jews, Russian Jews, Polish Jews, and all kind of Jews. The issue there is ethnicity more than it is race. Ethnicity is the glue holding that society together.

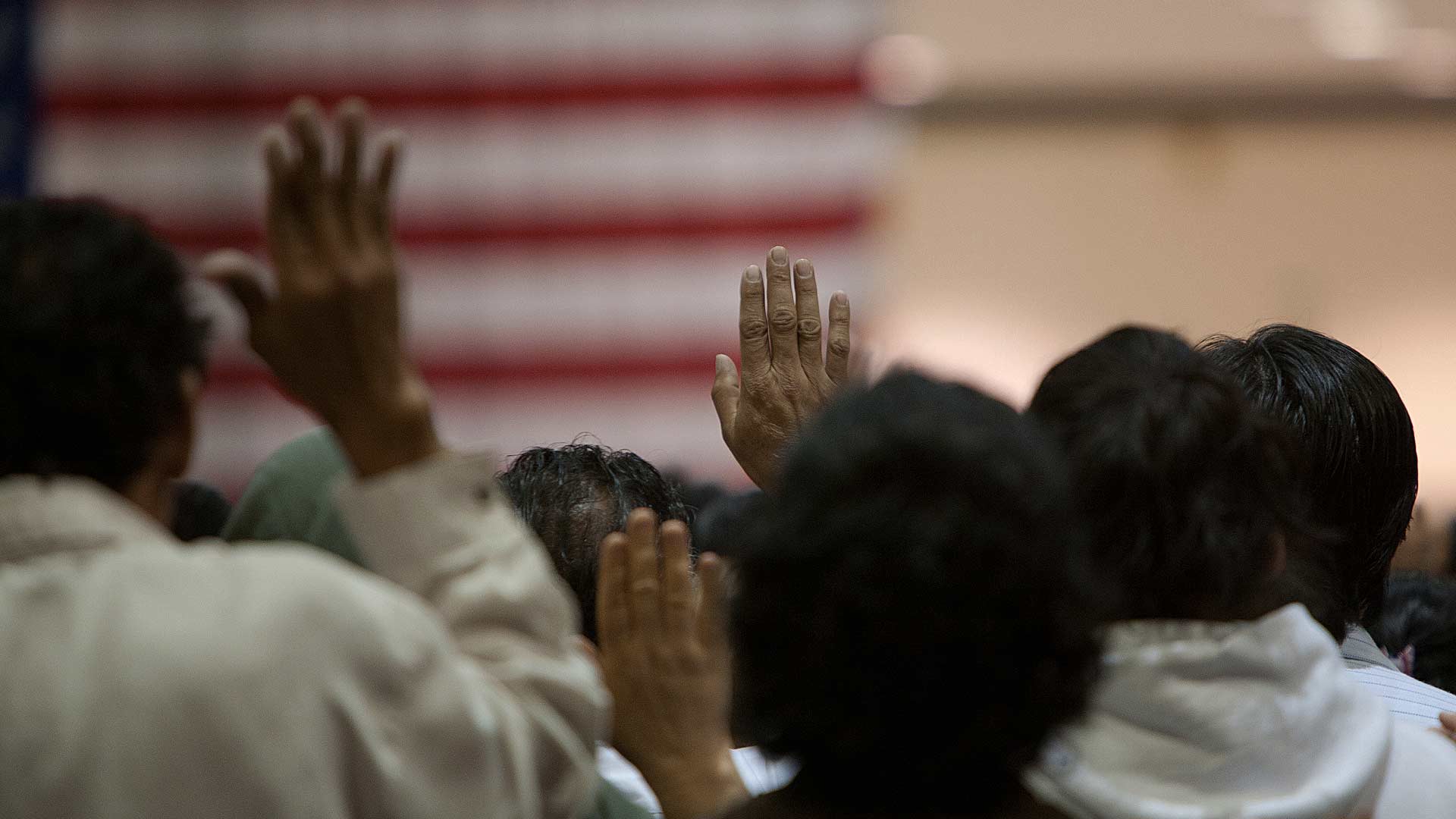

The glue that holds us together in the United States is that we all perceive ourselves as Americans, though that may mean different things to different people. There is no longer a need to feel as though everyone has to go into this big stew and become one big mush. Now it’s OK to taste the individual flavors of the potatoes, the carrots and the peas. But there is a new taste, too.

ALASKA WATCHMAN DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX

Historically, the term ”minority” refers to a people who constitute less than 50% of a broader population and are identified as a racial or ethnic group. Often, they have been the target of unfair treatment and have suffered disadvantages as a result. Thus, most Americans with ethnic ties to Europe would not be considered minorities, except for American Jews, and, for example, someone like myself, a foreign-born political refugee, who has suffered a history of persecution by a former totalitarian regime.

For decades, minority groups and foreign-born American citizens have faced poverty, discrimination, and the prejudices of people who have viewed them as different, less than equal and threatening. Despite the fact that America is a nation of immigrants, and America has been nourished throughout its history by ideals and traditions of different ethnic groups, this treatment often continues to prevail in our everyday life by means of direct and indirect ignorance, prejudices and stereotypes.

It is imperative, however, to maintain and protect a cohesiveness.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau statistics of 2019, a little under 40% of the total population was either non-white or Hispanic; and minorities and new immigrants comprised about 55% of the labor force and 45% of all elementary and secondary school students in the United States. Actually, these non-white minority groups will comprise a majority of our population in about 25 years.

Taking this demographic data into account, core cultural values, norms of traditional behavior, moral principles and beliefs, and the ethnic landscape of our society are changing rapidly. It is imperative, however, to maintain and protect a cohesiveness, integrity and core cultural values of our diverse nation — a required necessity for cultural survival of any complex society.

‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ We are dangerously close to toppling our house.

As a prominent American anthropologist Ruth Benedict once stated: “The purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences.” Thus, to apply Benedict’s vision and words to today’s reality in America, prejudiced behavior, radical Marxist ideology and divisive rhetoric of “white privilege” theory, with its outgrowth of “Black Lives Matter,” “systemic racism,” “structural racism” and today’s “ANTIFA,” should not have a place in our political, educational and socio-economic systems. Certainly, these so-called progressive narratives should not be used to advance political agendas.

I have always been fascinated by the phrase “United We Stand” and its subsequent juxtaposition “Divided We Fall.” Or, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” We are dangerously close to toppling our house.

The writer was raised in the former Soviet Union before settling in the U.S. in 1978. He moved to Juneau in 1986 where he has taught Russian studies at the University of Alaska, Southeast. He is now director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center and has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography.

The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the Alaska Watchman.