History does not repeat. Yesterday will never be today or tomorrow, but historic patterns do repeat. History shows a pattern of nations’ emergence, growth and decline. It provides facts and allows us to search for underlying causes of historic events.

Elected government officials, policy makers, educators and society at large must clearly understand that ignorance, irresponsible government mandates and ignorance of historic patterns may create irreversible socio–economic schisms.

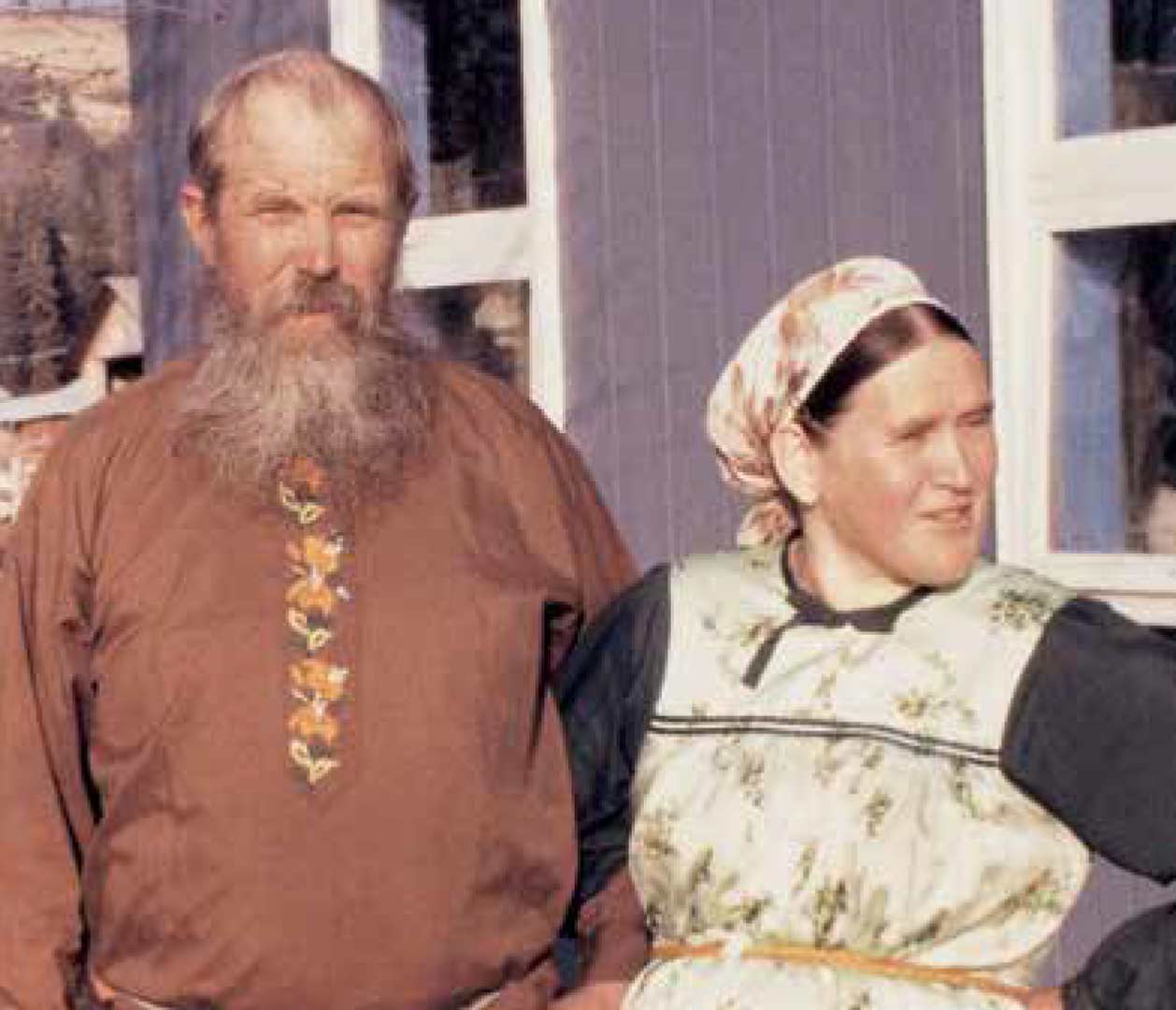

The “Great Schism” of the Russian Orthodox Church serves as a living example of possible societal disasters and dislocation of millions of people. Russian Old Believers in Alaska, and elsewhere, are victims of this type of authoritarian and tragic historic event.

This column is a revised extract from my book, “Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers.”

The Mongolian domination, the shift of Russian statehood northward, and isolation of the Russian Orthodox Church from Byzantine theology, led to a decline of learning, which resulted in many errors in translating the Holy Texts from Greek into Church Slavonic. As early as the mid–16th century, attempts were made to correct the errors and attain conformity in rituals.

Only in the mid–17th century (1652–66), however, were the Russian Orthodox Church and all of Russia shaken to the core by what has since been called the “Great Schism” (Raskol). At the time, Nikon (1605–1681), a strong–minded patriarch, scholar and strict disciplinarian, wanted to correct the Holy Texts by introducing revisions in church books and liturgical practice, which the masses had used since the inception of Christianity in Russia in the 10th century. These changes revised church books where errors, marginal notes, and mistranslations had occurred over time. They also included revising several of the actions the faithful and illiterate peasants had internalized as part of the mystical context of their worship.

Nikon demanded that church practices conform at every point to the standard of the four ancient patriarchates, and that the Russian service books be altered wherever they differed from the Greek.

In 1653, Nikon sent a memorandum to churches across the land, instructing them in various revisions. Among major points of contention were: (1) How many fingers would be used to make the sign of the cross – two or three. The conservatives maintained that the sign of the cross with two fingers rather than three (the latter being the proposed reform) signified the dual nature of Christ. They cited many old icons where Christ and the saints were depicted with the two-fingered sign.

Old Believers thought that the Russian state was of the Antichrist and that the end of the world was at hand.

The three-fingered sign was intended to acknowledge the Holy Trinity. But this was considered by the conservative dissenters to represent Greek heresy; (2) the spelling of Jesus’ name, (3) whether “Alleluia” should be sung two or three times; (4) the retention of certain words and phrases in the Creed, (5) the number of hosts to be used in the liturgy; and (6) whether the priests should walk around the altar with or against the passage of the sun. This policy was aimed at those who regarded Moscow as the Third Rome and Russia as the stronghold and norm of Orthodoxy.

By establishing Greek practices in Russia, Nikon also pursued a second goal: to make the church supreme over the state. The Russians certainly respected the memory of the Mother Church of Byzantium from which they had received the faith, but they did not feel the same reverence for contemporary Greeks.

This may seem a trivial matter, but in the eyes of simple believers a change in a symbol constituted altering the faith.

Changes proposed by the Patriarch Nikon became the focus of opposition for those who held onto the old rituals. Labeled Raskolniki (people of the schism) by the reformers, they called themselves Old Believers (Starovery) or True Believers. Old Believers stubbornly pointed out that they were not splitting from the church, but that the reformers were drawing the church away from the true Orthodox rituals. No doctrinal point, however, was involved in the schism.

Though the schism was basically a religious phenomenon, it involved broader socio-political factors.

Many Russians stubbornly opposed the changes in rituals simply because Nikon promoted them. Others refused to conform to them, strongly questioning the authority of the patriarch to make such alterations. After all, the Orthodox Church, with the purity of its apostolic succession traced to St. Andrew, had protected itself from the “Roman Heresy” and had steadfastly remained untainted while Constantinople, the capital of Byzantium, or the “Second Rome,” fell into the hands of the Turks in 1453. While Moscow increased its power, independence and territories, in particular the acquisition of Kiev in 1667, many favored the concept of Moscow as the “Third Rome.” Having preserved its purity, while others had lost theirs, Russian Orthodoxy was believed by the Russians to be the only remaining survivor of the true church and they counseled a deliberate withdrawal from Greek tutelage.

Given these considerations, how could Patriarch Nikon dare to order changes? Opposition to the innovations was also tied to an important psychological factor: the traditional forms and familiar routines provided a sense of security. The people, insecure amid chronic religious disorders, bitterly opposed new and further efforts to uproot old rituals.

Old Believers thought that the Russian state was of the Antichrist and that the end of the world was at hand. They also believed that the Antichrist’s evil spirit was at work through Nikon and the Tsar Alexis himself was the Antichrist. This belief demanded resistance to the state and the official church — the instruments of the Antichrist. For, in both symbolic and practical terms, the faithful were not to submit to his power.

Though the schism was basically a religious phenomenon, it involved broader socio-political factors. In order to understand this historical event, one must realize that the church was not an isolated institution within the state, but part of the ideological norms and values of 17th-century Russia.

Rebellions against the authority of higher churchmen were frequent, and there was persistent opposition from them toward efforts to increase and centralize clerical authority.

Two distinct classes of clergy in the Russian Orthodox Church controlled social and political attitudes. Parish priests, known as white clergy because of their white garments, represented the common people and peasants in many ways. They served two masters – the village commune that selected and paid them and limited their actions, and the higher ecclesiastics by whom they were taxed.

The higher clergy, called black clergy, were all monks. They were the servants of the tsar, just as the white clergy served the villages. White clergy could never hope for promotion to places of power and wealth, such as the bishoprics and archbishoprics, since these were the monopoly of black clergy.

Between the black and the white clergies existed an almost unbridgeable gap and constant controversies. Rebellions against the authority of higher churchmen were frequent, and there was persistent opposition from the white clergy toward efforts to increase and centralize clerical authority. These efforts climaxed during the Patriarchate of Nikon (1652–58).

In fact, he was not the first to attempt to adopt changes in the Russian Church, nor did his efforts initially arouse opposition. But his reforms became the immediate cause of the “Great Schism,” partly because he had many personal enemies who used the controversy to eliminate Nikon from the center of Church authority. In 1658, Nikon withdrew into semi-retirement but did not resign the office of Patriarch. For eight years, the Russian Church remained without an effective head, until Tsar Alexis requested a great Council in Moscow between 1666–1667 over which the patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch presided.

The specific opposition to Nikon’s reform was at first confined to the higher (black) clergy, but under the leadership of Nikita Dobrynin and Archpriest Avvakum, the movement spread widely to the streets of Moscow and beyond. Avvakum and his followers regarded the tiny changes in spelling suggested by Nikon as a cardinal criterion of Christianity as such, and a portent of the coming of the Antichrist.

By mobilizing Russians against the official church and against Nikon, the early Old Believers helped lay the intellectual foundations of Old Belief and Old Russia Text.

Old Believers had a large following, which included both ordinary laymen and prominent members of the local church hierarchy.

The schism and purge also weakened the church and later made it easier for Peter the Great (1672–1725) to subordinate it in order to strengthen his autocracy and enforce new socio-political reforms

As a result of the popular rebellion against the church, Patriarch Nikon lost the favor of Tsar Alexis and his enemies removed him from control of the church, but the quarrel raged on between those who supported the changes and those who opposed them. Finally, the Church Council called in 1666–1667 decided in favor of Nikon’s reforms, but against him personally. Violence began almost at once and was marked by monstrous cruelties for four decades. Nikon’s changes in the service books and above all his ruling on the sign of the Cross were confirmed, but Nikon himself was deposed and exiled; a new patriarch was appointed in his place. The Council was, therefore, a triumph for Nikon’s policy of imposing Greek practices on the Russian Orthodox Church, but a defeat for his attempt to set the patriarch above the tsar.

Tsar Alexis sided with reformers and eventually approved the reforms, making refusal to conform not just an offense against the church, but a civil offense as well. He openly waged campaigns against conservatives.

Tsarist approval of the church reforms involved political motivations, such as national independence from the Byzantium and Greek Orthodoxy influence, governmental control of the ideological institutions, the long process of territorial growth of the Russian state and continuing efforts of political and economic centralization of Russian lands under Moscow authorities.

The schism and purge also weakened the church and later made it easier for Peter the Great (1672–1725) to subordinate it in order to strengthen his autocracy and enforce new socio-political reforms. Peter the Great identified himself with the official church by placing it under the rule of the absolutist state. In 1721, the tsar abolished the patriarchate as well as the church council and assumed the position as supreme head of the church through control of a chief procurator called “The Tsar’s Eye.” Peter sought not only to deprive the church of leadership, but also to eliminate it from any participation in social and government work.

Old Believers took refuge in undeveloped areas of the country, thereby avoiding persecution for their continued lack of obedience to the tsar’s commands.

Because the power of the tsar stood behind the Church Council of 1666–1667, the schismatics were in fact rebels against both church and state. To oppose imminent unrest among Russian masses, the government searched for and punished the most active rebels. Archpriest Avvakum, the most instrumental and effective leader of the Old Believers, was burned at the stake in 1682 after having been exiled for 10 years and imprisoned for 22. From then on, the decree of 1685, issued by the Regent Sophia, sanctioned burning at the stake and jailing or exiling those who preached old beliefs and refused to repent. In protest, whole communities of Old Believers locked themselves in their wooden chapels and set them on fire, preferring self-inflicted death.

A prominent Russian historian of the 19th century Nikolay Kostomarov (1817–1885,) preserved a graphic account of a case which manifests how and why the Raskol became so contentious:

“It was in Tumen, a town in Western Siberia; time, Sunday morning. The priests were celebrating the mass in the cathedral on the lines of the new missals, as usual. The congregation was listening calmly to the service, when, at the moment of the solemn appearance of the consecrated water, a female voice shouted, “Orthodox! Do not bow! They carry a dead body; the water is stamped with the unholy cross, the seal of Antichrist. The speaker was a female Raskolnik, accompanied by a male coreligionist of hers, who thus interrupted the service. The man and woman were seized, knouted in the public square, and thrown into prison. But their act produced its effect. When another Raskolnik, the monk Danilo, shortly after appeared on the same spot and began to preach, an excited crowd at once gathered around him. His words affected his audience so deeply that girls and old women began to see the skies open above them, and the Virgin Mary, with the angels, holding a crown of glory over those who refused to pray as they were ordered by the authorities. Danilo persuaded them to flee into the wilderness for the sake of the true faith. Three hundred people, both men and women, joined him, but a strong body of armed men was sent in pursuit. They could not escape, and Danilo seized the moment to preach to them, and persuade them that the hour had come for all of them to receive “the baptism of fire.” By this he meant they were to burn themselves alive. They accordingly locked themselves up in a big wooden shed, set fire to it, and perished in the flames—all the three hundred, with their leader.”

ALASKA WATCHMAN DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX

Another graphic account of Old Believer opposition by means of collective self-mutilation was described by French historian Henri Troyat:

“Some sectarians slept in coffins, others flagellated each other, still others condemned themselves to eternal silence, castrated themselves, cut one another’s throats, or locked themselves up in a house with their families, set fire to piles of straw, and perished in the flames singing hymns to be sure of entering paradise. Under pressure from their fanatical parents, children would say: ‘We will go to the stake; in the other world we will have little red boots and shirts embroidered with gold thread; they will give us all the honey, nuts, and apples we want; we will not bow down before the Antichrist.’ Soldiers were sent to prevent these autos-da-fe [ritual of public penance]. But their arrival only precipitated the madness of the fanatics, who would throw themselves by hundreds into the purifying flames. The most reasonable of the schismatics sought refuge in the forests, organized themselves into autonomous communities, and lived soberly by their labor, refusing the aid of the priests and professing among themselves the faith of the ancestors. Thus, Russians’ heresy included a whole psychological spectrum, from demented excesses of some to the quiet protest of others.”

Although many were purged, the movement to preserve Old Orthodox rituals still persisted. Many risked persecution, exile or death rather than give up old rituals and traditions. As the government embarked upon the repression, most rebels fled from the major population areas of the Russian State.

Their protest was soon to be eclipsed by other problems that beset the growing and developing Russian nation state. As Russia lumbered through its wars and social strife, the Old Believers took refuge in undeveloped areas of the country, thereby avoiding persecution for their continued lack of obedience to the tsar’s commands. Periodic reprieves and attempts to re-incorporate these people met with only moderate success. Thus, Old Believers came to represent the groups that rejected the church reforms and found themselves in opposition to the established Orthodox Church and Russian tsarist authorities.

Indeed, lessons and historic patterns must be learned from the “Great Schism” in order to apply them to modern American socio-economic disputes.

1 Comment

Lotta sick BS took place in Russia under the church leadership and the Tsars. Simple lesson , God created government and the church as his institutions for the good of the people, not for their harm and he never intended for them to be joined OR have one controlling the other. Next lesson, church hierarchy is DANGEROUS and the local body of believers is meant to be controlled by,gasp, the local body of elders.